This is the second installment in an ongoing and multipart series on race, racism, and biological anthropology. Why talk about race if it isn’t biological? You can find out in Part 1 here: https://bonesandbioanth.com/why-race-isnt-biological-part-1-an-introduction/

One of the overarching fields of inquiry within biological anthropology is the study of human variation, and one of the most noticeable ways humans vary is skin color. This is often what we think about first when we think about race, but race is not the same thing as physical variation. Race as we know and experience it is a sociocultural construct, or an idea that’s been created and upheld by people of a society or culture. We’ll get into why and how race was created in a future post, but for now let’s focus on the biological basis for race, or the lack thereof. While race is very real socioculturally, it is not biological as we sometimes tend to forget. Let’s deconstruct why that is.

Phenotypic Human Variation

In order to understand race we first need to understand what human variation is. This will help us understand why variation is not the same thing as race. Variation describes the differences that exist between individuals or populations of the same species. All species have some level of variation. The most easily noticeable variations are physical. A phenotype describes the physical traits or differences that we can observe. This is the outward appearance of an organism. Expressed physical traits such as size, color, shape, etc. are phenotypic traits. These can be the result of underlying genetics or environmental factors, but most often they are a combination of both. Phenotypic variation therefore describes all the possible phenotypes that can exist in a population of the same species. Humans have noticeable phenotypic variations, such as different skin colors, but have relatively little underlying genetic differences influencing phenotype.

Phew! Are you still with me? Let’s take it a level deeper.

Genetic Human Variation

Despite appearances, humans as a species have remarkably low genetic variation when compared with other mammals. Most of the differences between individuals consists of our biological sex and any phenotypic variations. Genetically we are all very similar, sharing 99.9% of our genetic material. That’s a lot! In contrast, our closest nonhuman primate relative, the chimpanzee, has roughly 4 to 10 times more genetic diversity. In fact, groups of chimps living in Africa are more genetically different from each other than groups of humans living on completely different continents.

The degree of interracial variability makes “race” a poor surrogate for nearly any feature: in a genetic sense, an African man from Nigeria is so “different” from another man from Namibia that it makes little sense to lump them into the same category.”

SIDDHARTHA MUKHERJEE, AUTHOR OF THE GENE: AN INTIMATE HISTORY

There is also more genetic variation within so-called racial groups than between them. Approximately 85-90% of genetic diversity varies between individuals within these groups, with 5-15% variation occurring between groups. What does this mean? Two people who look like they have the same skin color can have very different genes from each other. Likewise, two people who look very different from each other can actually be very genetically similar. There is no genetic basis for racial categories because there is not a ‘gene’ for race. Race isn’t biological.

The two humans pictured above may look very different and yet they are fraternal twins, sharing the same amount of genetic material as siblings, roughly 50%. This is normal genetic variation on par with twins having different eye colors, and yet we tend to sensationalize variation in complexion as equivalent to belonging to different races. How can this be? Racial identity is fluid and subjective, not biological.

Discontinuous Variation

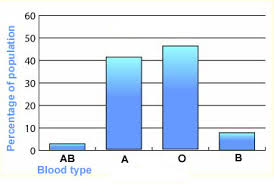

Now let’s look at two types of variation. Discontinuous variation describes traits that can be divided into a set number of discreet individual categories. You either have the trait or you don’t. An example of a discontinuous trait would be blood type. You are either type A, B, AB, or O. There are no in-between categories. You can only fall into one of these discreet groups. Discontinuous traits are the result of one or only a few genes. They are caused by genetic factors alone and are not influenced by the environment.

Continuous Variation

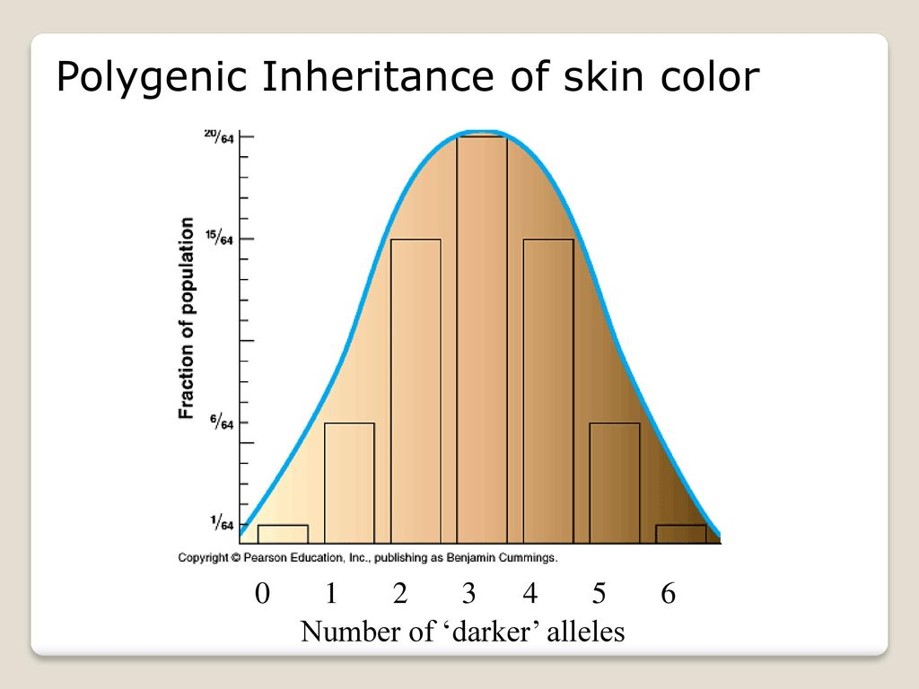

Continuous variation describes traits that do not divide easily into a set number of discreet individual categories. Traits that are continuous vary on a gradient, with many intermediates between the extremes. For example, there exists every shade of hair color between the extremes of lightest blonde and darkest black. Continuous traits vary in amount, not in type. For example, melanin (the pigment that determines skin color) is present in human skin at varying amounts, creating a gradient of skin colors. The more melanin present, the darker the skin pigmentation.

Continuous variation is controlled by more than one gene and can be the result of genetic factors, environmental factors, or both. What does this mean? There is no single gene that codes for skin color but rather combinations of 13+ genes discovered so far. The light skin tone of Northern Europeans is not caused by the same genes that cause the light skin tone of Northeastern Asians, although both populations may appear to have the same skin tone.

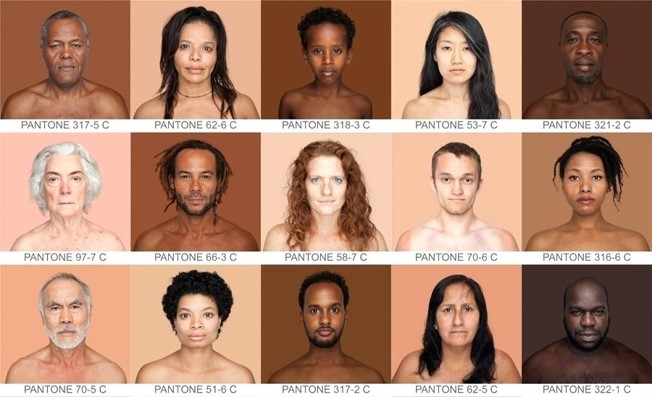

One of the major misconceptions supporting the biological race concept is that humans naturally divide into a small number of distinct races. As we’ve just learned however, the so-called racial trait of skin color is continuous and cannot be divided easily into discreet categories. Instead of categories, human skin color is a gradient with many shades existing between the two extremes. The more we’ve come to understand the biology behind human variation, the less the idea of biological races is supported.

Kate Keller (McElvaney)

References:

Cover image by Angélica Dass, artist behind the “Humanae” photo project: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/4000-skin-colors-in-pantone-squares-1254683

TEDTalk by Angélica Dass, artist behind the “Humanae” photo project: https://www.ted.com/talks/angelica_dass_the_beauty_of_human_skin_in_every_color

https://www.vox.com/2017/1/29/14377940/biracial-twins-black-white-race-identity

This ongoing series has been enlightened in part by The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee, Close Encounters with Humankind: A Paleoanthropologist Investigates Our Evolving Species by Sang-Hee Lee, The Coexistence of Race and Racism: Can They Become Extinct Together? by Janis Hutchinson, and many others.

Always interesting! Can’t wait to read more!